University of Calgary

This clever new refrigerator keeps food cold without electricity

Good job, science!

It’s easy to take that hulking great white beast of a machine in our kitchens for granted, but for the 1.3 billion people in the world who are living without electricity, a working refrigerator is not an option. So a team of students in Canada has invented a cooling device that not only works without any electricity whatsoever, it’s also cheap and portable, making it ideal for those in remote and rural areas who struggle to keep their produce fresh. "We thought it would be good to decrease the amount of food waste in the world, and we came up with this design because it's easy to build and the materials are relatively cheap," one of the students, Michelle Zhou from the University of Calgary, told CBC News.

Dubbed the WindChill Food Preservation Unit, the device connects an air tube to an evaporation chamber, which connects to a sealed refrigeration chamber that looks a lot like an esky, the contents of which are cooled through the process of evaporative cooling. It works by passively drawing in warm ambient air through the funnel, which is fed into a pipe that’s been buried underground. This already starts to cool down the air before it's fed into coiled cooper pipe that’s been immersed in water in the evaporation chamber. The evaporation process is helped along by a small, solar-powered fan. The water evaporating around pipe chills the air inside, and this is then fed back underground before entering the refrigeration chamber. The invention won first place in the student category of the 2015 Biomimicry Global Design Challenge, which asks researchers and students to come up with improvements to the global food system inspired by nature. The University of Calgary team says its invention was inspired by everything from coral and kangaroos to bees and elephants - think siphoning air in via elephant ears and keeping things cool underground like termite tunnels. The next step will be to improve the design to achieve a consistent 4.5 degrees Celsius temperature in the refrigeration chamber, which is what’s needed to keep food from spoiling. "Anywhere from a quarter to half of the world's food goes to waste every year, and in rural populations - about 70 percent of the people in rural Africa don't have access to electricity," team member Jorge Zapote told CBC News. "So this at the moment uses a tiny bit of electricity from a solar panel, but the end design is to use zero electricity. So this could really help people in those areas."

http://www.sciencealert.com/this-clever-new-refrigerator-keeps-food-cold-without-electricity

25 October, 2015 - 03:09 Mark Miller

The Plague that brought down mighty empires is thousands of years older than thought

The Plague is far older than previously known and later changed to become much more virulent—so virulent that it may have contributed to the decline of Classical Greece and the Roman and Byzantine empires and later killed off 30 to 50 percent of Europe’s population, a new study says.

The bacteria that causes the Plague, Yersinia pestis, diverged from the less-pathogenic Y. pseudotuberculosis bacterium about 5,783 year ago. That divergence, and therefore the bacteria’s possibility of infecting humans, is much earlier than scholars previously estimated.

While the Plague would go on to kill tens of millions of people in Europe and Asia, researchers have found DNA of Y. pestis in the teeth of a Russian person who died 5,000 years ago. They say that although the plague doesn’t appear to have been as prevalent or as virulent in the Bronze Age, even then it may have triggered migrations of populations in Europe and Asia and caused population decreases.

Writing the in the journal Cell, biologist Simon Rasmussen of the University of Denmark and his team say: “Here, we report the oldest direct evidence of Yersinia pestis identified by ancient DNA in human teeth from Asia and Europe dating from 2,800 to 5,000 years ago. … We find the origins of the Yersinia pestis lineage to be at least two times older than previous estimates. … Our results show that plague infection was endemic in the human populations of Eurasia at least 3,000 years before any historical recordings of pandemics.”

“However, based on the absence of crucial virulence genes, unlike the later Y. pestis strains that were responsible for the first to third pandemics, these ancient ancestral Y. pestis strains likely did not have the ability to cause bubonic plague, only pneumonic and septicemic plague,” they wrote.

Bubonic plague is transmitted by fleas, so this means the Plague likely was transmitted solely by humans earlier in its epidemiology. Around the late second millennium and early first millennium BC, the plague began to be spread by fleas via rats—an extremely rapid mode of transmission. Pneumonic plague affects the lungs, and septicemic plague affects the blood.

Phys.org, reporting on the new research, wrote that the Books of Samuel in the Old Testament of the Bible tell of a plague among the Philistines in 1320 BC. The people suffering from it had swellings in the groin. The World Health Organization says such swellings are consistent with bubonic plague. The authors say this may indicate that the highly lethal bubonic plague originated in the Middle East.

The bacteria that causes the Plague, Yersinia pestis, diverged from the less-pathogenic Y. pseudotuberculosis bacterium about 5,783 year ago. That divergence, and therefore the bacteria’s possibility of infecting humans, is much earlier than scholars previously estimated.

While the Plague would go on to kill tens of millions of people in Europe and Asia, researchers have found DNA of Y. pestis in the teeth of a Russian person who died 5,000 years ago. They say that although the plague doesn’t appear to have been as prevalent or as virulent in the Bronze Age, even then it may have triggered migrations of populations in Europe and Asia and caused population decreases.

Writing the in the journal Cell, biologist Simon Rasmussen of the University of Denmark and his team say: “Here, we report the oldest direct evidence of Yersinia pestis identified by ancient DNA in human teeth from Asia and Europe dating from 2,800 to 5,000 years ago. … We find the origins of the Yersinia pestis lineage to be at least two times older than previous estimates. … Our results show that plague infection was endemic in the human populations of Eurasia at least 3,000 years before any historical recordings of pandemics.”

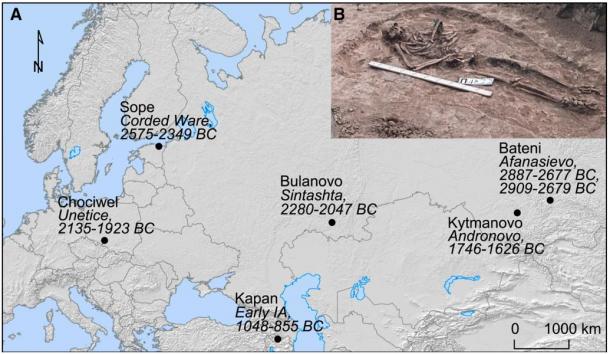

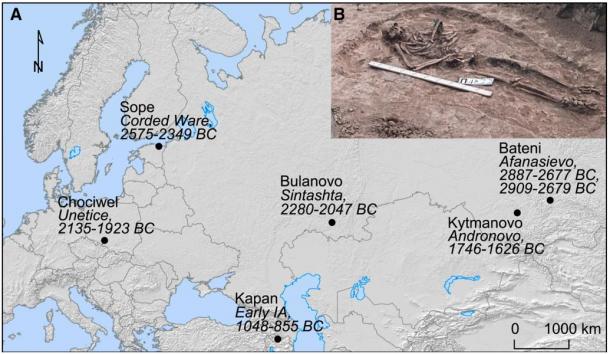

This map of Eurasia shows where and in which cultures the plague bacteria were found and dated; the inset show a burial from the Bulanovo site. (Images from Cell, photo by Mikhail V. Khalyapin)

The Plague, which can be transmitted from humans to humans or from fleas to humans, has broken out in three pandemics in history. They werexSee all ReferencesTreille and Yersin, 1894 the Plague of Justinian (541–544 AD), which continued intermittently until about 750 AD; the Black Death in Europe, which included the first pandemic from 1347–1351, the Great Plague from 1665–1666 and into the 18th century; and the Third Pandemic, which emerged in China in the 1850s and erupted into a major epidemic in 1894, then spread worldwide as a series of epidemics until the mid-20th century. Earlier plagues, from 430-427 BC in Athens and a plague in the Roman Empire from 165-180 AD may or may not have been caused by Y. pestis, the authors say.

Scanning electron micrograph of a flea, which carry disease, including the plague, that infect people when they bite them. (CDC photo/Wikimedia Commons)

By sequencing Y. pestis DNA, the researchers determined the bacterium underwent genetic changes that increased its virulence and led to far more deaths and catastrophic impacts on society that may even have contributed to the collapse of empires. The authors wrote in Cell:The consequences of the plague pandemics have been well-documented and the demographic impacts were dramatic. The Black Death alone is estimated to have killed 30%–50% of the European population. Economic and political collapses have also been in part attributed to the devastating effects of the plague. The Plague of Justinian is thought to have played a major role in weakening the Byzantine Empire, and the earlier putative plagues have been associated with the decline of Classical Greece and likely undermined the strength of the Roman army.They concluded in their article that plague was common 3,000 years earlier than historic texts indicate and may have caused die-offs of humans in the late fourth millennium BC and into the early third millennium BC across Eurasia.

“However, based on the absence of crucial virulence genes, unlike the later Y. pestis strains that were responsible for the first to third pandemics, these ancient ancestral Y. pestis strains likely did not have the ability to cause bubonic plague, only pneumonic and septicemic plague,” they wrote.

Bubonic plague is transmitted by fleas, so this means the Plague likely was transmitted solely by humans earlier in its epidemiology. Around the late second millennium and early first millennium BC, the plague began to be spread by fleas via rats—an extremely rapid mode of transmission. Pneumonic plague affects the lungs, and septicemic plague affects the blood.

Phys.org, reporting on the new research, wrote that the Books of Samuel in the Old Testament of the Bible tell of a plague among the Philistines in 1320 BC. The people suffering from it had swellings in the groin. The World Health Organization says such swellings are consistent with bubonic plague. The authors say this may indicate that the highly lethal bubonic plague originated in the Middle East.

http://www.ancient-origins.net/news-science-space/plague-brought-down-mighty-empires-thousands-years-older-thought-004310#ixzz3plwCFidG

Louisville judge questioned for dismissing juries based on lack of minorities

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) – Unhappy with the number of potential black jurors called to his court last week, Jefferson Circuit Court Judge Olu Stevens halted a drug trial and dismissed the entire jury panel, asking for a new group to be sent up.

“The concern is that the panel is not representative of the community,” said Stevens, who brought in a new group of jurors despite objections from both the defense and prosecutor.

And this wasn’t the first time Stevens, who is black, has dismissed a jury because he felt it was lacking enough minorities. Now the state Supreme Court is going to determine whether the judge is abusing his power.

On Nov. 18, after a 13-member jury chosen for a theft trial ended up with no black jurors, Stevens found it “troublesome” and dismissed the panel at the request of a defense attorney.

“There is not a single African-American on this jury and (the defendant) is an African-American man,” Stevens said, according to a video of the trial. “I cannot in good conscious go forward with this jury.”

A new jury panel was called up the next day.

After that, the Jefferson County Commonwealth’s Attorney’s Office and Attorney General asked the Kentucky Supreme Court to look at the issue and see if Stevens has the authority to dismiss jury panels because of a lack of minorities. And last month, the high court agreed to hear arguments.

Jefferson County has long had a problem with minorities being underrepresented on local juries. Several black defendants have complained over the years that they were convicted by an all-white jury - not of their peers.

The Racial Fairness commission - a group made up of local judges, lawyers and citizens - has studied the issue for years, monitored the make-up of jury panels and found them consistently lacking in minorities.

For example, in October, 14 percent of potential jurors were black, far below the estimated 21 percent for all residents of Jefferson County, according to records kept by the commission. In September, 13 percent of potential Jefferson County jurors were black.

“It’s a problem,” said Appeals Court Judge Denise Clayton, head of the commission. “We are not hitting that representation.”

But should judges take it upon themselves to try and ensure a more representative jury?

Stevens said through a secretary at his office that he has no comment.

Commonwealth’s Attorney Tom Wine declined to comment. But in the November case, prosecutors argued the jury panel was chosen at random, as is typically done.

And prosecutors said dismissing a jury after they had learned about the case and sending them back to be with the original pool could taint jurors.

But Stevens said both sides should “erase” what happened with jury selection from their minds and pretend it didn’t happen. In fact, the judge forbade each side from making any motions based on anything the previous jurors had said and referred to the questioning of the second batch of jurors as the first day of trial, according to court documents.

In requesting the Supreme Court hear the issue, Assistant Commonwealth’s Attorney Dorislee Gilbert argued that other judges “may feel societal, political, and other pressures” to dismiss a jury for lack of minorities if allowed.

And Gilbert said that there was no proof the jury in the November case could not be fair and impartial just because of their race.

The judge “struck the jury based on nothing more than unsupported fear or impression that the jury might not be fair because of its racial makeup,” Gilbert wrote in the case, commonwealth vs. James Doss. “There was no consideration of whether the commonwealth or the citizens who had sacrificed of their own lives to make themselves available for jury service had any rights or interests in continuing to trial with the jury as selected.”

In the recent case, on the second day of the drug trial on Oct. 14, Stevens said he was concerned that the panel of jurors attorneys were to choose a jury from included 37 white people and only three black citizens. And two of the three potential black jurors had already been eliminated.

The defense attorney, Johnny Porter, suggested ensuring that the lone remaining black member of the panel makes the final jury.

Stevens told both sides about the Nov. 18 trial, how the second panel of jurors he called up included four black citizens and was more representative.

“We’ve already done this one time,” Stevens said. “So right off the bat, you’ve got a blueprint and we can be a lot more efficient, in theory.”

http://www.wdrb.com/story/30308688/louisville-judge-questioned-for-dismissing-juries-based-on-lack-of-minorities

No comments:

Post a Comment